The jury is still out on the productivity benefits, if any, of Working from Home (“WFH”). A 2020 Australian survey of employers and employees found that most respondents considered productivity to be “about the same”, with employers slightly more skeptical (Productivity Commission Report, 2021). A well known 2015 study of Chinese travel agents found a 13% increase in performance with WFH, of which 9% was attributable to working more minutes and 4% was attributable to increased productivity (Bloom et al, 2015). A mid pandemic study of a large Asian IT firm found that productivity declined by 8 - 19%, however this may also be partially attributable to schools being closed, and WFH models not being fully optimized (Gibbs, Mengel and Siemroth, 2021). In a research project at Macquarie Business School Ashley Alcock analysed the impact of differing work models on productivity in a Bangkok based recruitment firm. He found that, on average, professionals were more productive in the office than at home, but there was variation in results for individual cohorts. Most notably, new employees who worked from home were only 50% as productive as new employees who worked in the office. However, more experienced employees and working parents who chose to work from home had similar levels of productivity to their office-based counterparts. Importantly, productivity was significantly improved when employees were able to select whether they worked from home or the office (MQ Lighthouse, 2021).

The most significant benefit for employees is the saving in commute time. Other key benefits include the ability to better manage time and concentrate. Even though hours worked may be longer, the overall benefits to work life balance and flexibility are valued by a large number of employees. A recent EY survey of 16,000 employees across 16 countries found that 54% would consider leaving their job post-COVID-19 pandemic if they are not afforded some form of flexibility in where and when they work [1]. Some employers are embracing WFH opportunities, with Facebook and Atlassian prime examples. However, WFH can also have costs. Most significant is the negative impact on the quality of collaboration, and on workplace culture, networking and potential for innovation. A pre pandemic study of 259 European businesses found that higher WFH levels had adverse impacts on the productivity of other employees, and that team productivity was adversely affected by higher levels of WFH (Van der Lippe and Lippenyi, 2019). The potential for shirking, and the increased managerial effort on co-ordination are also potentially significant downsides of WFH. David Solomon, Chairman and CEO of Goldman Sachs summarised his view on WFH as follows: “WFH is an aberration that we are going to correct as quickly as possible”.

Knowledge based industries, including the financial sector, offer the best potential to provide WFH options to employees. The ABS April 2021 survey of Business Conditions and Sentiments found that 69% of employees in the Finance and Insurance Services industry were working from home, the highest level of any industry. It is a long term issue that each financial sector employer will need to address. While productivity is an important criterion, decisions will need to be made in the context of emerging employee preferences. Fully developed WFH models, and a work from anywhere model, may also enhance employment opportunities for a diverse workforce, and may also open up a wider pool of potential employees.

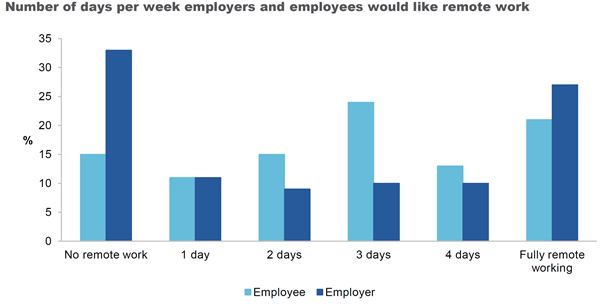

The evolving consensus is that a hybrid model is the best way to manage the tradeoffs of WFH. The Productivity Commission reports a survey (see chart below) that found that 85% of employees prefer at least one day of WFH, with just under 40% wanting either two or three days. Employer preferences also covered the spectrum, with approximately one third of employers preferring a working model with no remote work, with a quarter preferring a fully remote model. [2]

Source: Productivity Commission Report, 2021 Working from home research paper. Figure 2.5.

The Macquarie Business School study highlights that solutions will need to be company, and possibly employee, specific. Maroš Servátka, Professor of Economics at MQBS, advises that “each company will need to find their own balance. Companies will have to be careful about who they allow to work from home, when, and under what conditions”. The Productivity Commission Report also concludes that the evolution of WFH will involve a process of “testing, negotiation, reallocation and learning”. The right to self-select is important to employees, and more experienced employees appear to value this more highly. Will these employees decide to leave employers who do not offer this flexibility, or will they accept lower wages in order to have the flexibility to work from home?

The evolution of the optimal model will require a commitment to flexibility, transparency and process re-design. Some processes which occur organically in a full “in the office” workplace model will need more formal structure in a WFH model. For example, if newer employees are required to spend more of their initial time “in the office” to facilitate the development of networks and culture etc, then more experienced employees will need to be committed to that practice. Furthermore, a WFH model will require the development of accountability and performance monitoring practices suitable to a work environment of distributed employees and possibly asynchronous working times. For example, productivity needs to be assessed at the team level, and employees preferring WFH need to recognise potential adverse impacts on overall team performance. Additionally, how we measure productivity may be challenged. Traditionally productivity is measured in terms of units per hour. However, the surveys suggest that under WFH employees are probably working longer hours and effectively allocating some of their saved commute time to compensate for loss of efficiency.

Given the apparent preferences of many employees to have WFH as part of their working model it is important for employers to attempt to develop policies that work for both employees and organisations. It will help employers win the war for talent and access a broader talent pool. The potential benefits to employee well being and the boost to economy wide productivity are surely worth some organisational and employee investment in making WFH workable.

Tony Carlton

Honorary Associate Professor, Macquarie University Business School

REFERENCES

Bloom, N., Liang, J., Roberts, J. and Ying, Z.J. (February 2016). Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol 130, No 1.

[1] EY. (May 2021). More than half of employees globally would quit their jobs if not provided post-pandemic flexibility, EY survey finds.

Gibbs, M., Mengel, F. and Siemroth, C. (July 2021). Work from home & productivity. Evidence from personal & analytics data on IT professionals. Becker Friedman Institute for Economics, Working Paper, No 2021-56. University of Chicago.

Macquarie University Lighthouse. (October 2021). Home or Office? New research reveals where workers perform best. Macquarie Business School.

[2] Productivity Commission, (September 2021). Working from home, Research paper, Canberra

BBC News. (February 2022). Goldman Sachs: Bank boss rejects work from home as the 'new normal'.

Van der Lippe, T, and Z. Lippenyi. (March 2020). Co workers working from home and individual and team performance. New Technology, Work and Employment.